cover 13

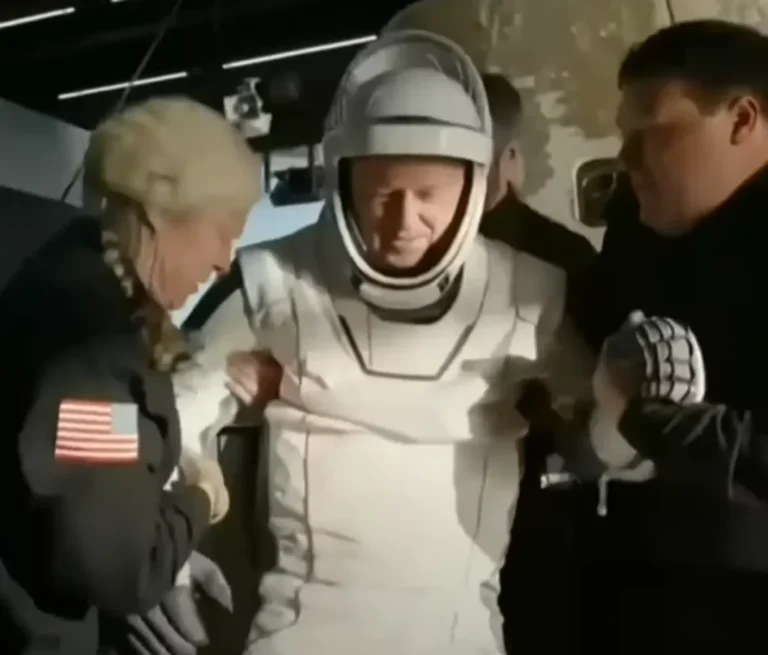

NASA astronauts Sunita “Suni” Williams and Barry “Butch” Wilmore have safely returned to Earth after an unplanned nine-month mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

Originally scheduled for an eight-day journey, the duo remained in orbit far longer due to malfunctions with their Boeing Starliner spacecraft, which prevented their timely return.

The prolonged mission has sparked extensive scientific discussions about the effects of extended spaceflight on human biology.

Researchers were particularly astonished by the notable physiological changes observed in both astronauts during their rehabilitation. New medical data and striking pre- and post-flight images have provided fresh insights into how long-duration space travel impacts the human body.

Williams and Wilmore’s return mission faced an unexpected complication that forced their spacecraft to remain grounded, delaying their re-entry to Earth.

What was initially planned as a mission of less than a week stretched into nine months, during which the astronauts contributed to scientific experiments and essential maintenance aboard the ISS.

The extended time in space subjected their bodies to the harsh effects of microgravity, known to cause significant physiological changes in humans.

While the public celebrated their safe return, scientists were quick to raise concerns about the potential health impacts of such a prolonged stay in space.

Prolonged exposure to microgravity leads to muscle atrophy, bone density loss, and fluid redistribution, all of which present serious health challenges for astronauts upon returning to Earth.

In just three weeks without gravity, astronauts can lose up to 20% of their muscle mass, requiring extensive physical rehabilitation post-mission.

Additionally, they experience a monthly bone density reduction of about 1.5%, increasing their susceptibility to fractures and symptoms similar to osteoporosis.

Fluid shifting toward the head causes facial swelling, vision impairment, and elevated intracranial pressure, which poses risks to long-term eye health.

Microgravity also affects the cardiovascular system, as the heart exerts less effort in space, leading to a slight reduction in heart muscle mass.

Astronauts often experience balance and coordination issues upon returning to Earth, as their spatial orientation systems struggle to readjust to gravity.

This prolonged mission has provided researchers with valuable insights into how extended spaceflight impacts human physiology over time.

Studies have shown that long-duration space travel can trigger accelerated or abnormal aging patterns—one of the most intriguing and concerning side effects of human space exploration.

According to the laws of relativity, time behaves differently depending on variations in gravitational force and velocity.

Astronauts aboard the ISS travel at approximately 28,000 kilometers per hour (17,500 miles per hour), causing them to experience time slightly differently compared to people on Earth.

This high-speed orbit results in a minor time dilation effect, where time passes more slowly for the astronauts than for those on the planet’s surface.

Over the course of a six-month mission on the ISS, astronauts age about 0.005 seconds less than people on Earth due to this relativistic phenomenon.

After spending nine months in orbit, Williams and Wilmore aged approximately 0.0075 seconds less than people on Earth due to time dilation.

A well-known example of this phenomenon is seen in the case of NASA astronauts Scott Kelly and his identical twin, Mark Kelly.

Scott, who spent significantly more time in space than Mark, returned to find himself effectively 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger than his Earth-bound brother, highlighting the subtle yet fascinating effects of time dilation in space travel.

Scientific measurements confirm that space exposure does, in fact, slow the aging process, although the effect is minimal.

While NASA images revealed noticeable physical changes in Williams and Wilmore after their time in space, their true biological age remained consistent with Earth-based aging standards.

Feature Image Credit: (NASA)

Здесь размещена увлекательная и практичная сведения по многим вопросам.

Гости могут обнаружить решения на актуальные проблемы.

Контент обновляются часто, чтобы вы могли получать новую подборку.

Удобная организация сайта помогает быстро отыскать нужные разделы.

купить клад

Широкий спектр тем делает ресурс полезным для многих читателей.

Каждый сможет выбрать материалы, которые нужны именно ей.

Наличие понятных советов делает сайт максимально ценным.

Таким образом, данный сайт — это интересный источник важной информации для любого пользователей.